By Andrew Sullivan

A confession: I’m much less afraid of Trump than I was a year ago. His rhetoric, his unfettered far-right agenda, his love of violence, and his loathing of constitutional limits during the campaign were indeed things to be terrified by. They still are. But those of us who were worried that the Constitution might not hold, and that liberal democracy was teetering on the edge of implosion, have so far, mercifully, been proven wrong.

The Founders turn out to have constructed a system designed to confront exactly this kind of despotic figure — and it has held up well, even with total GOP control of House and Senate, even in this dangerously liquid, hyperdemocratic modern world. The press has done its job of fact-checking, exposing, and opposing those in power (yes, Mr. Bannon, that is one part of its function in a democracy). The courts have resisted strongly. The opposition has seen a dramatic uptick in political and civic engagement. Even Trump’s own congressional party has splintered, impervious to the charisma of their hood ornament. The American public has not been swept up in a nationalist fervor and has tilted against much of Trump’s agenda — on health care and immigration in particular.

Yes, the Trump base remains invested in their antihero. In the poll of polls, he hasn’t dropped below 40 percent for more than a fraction of his time in office. And yes, he still taps into the most powerful currents in the world right now. But his overall popularity is still shockingly low for a newly elected president. And his sad lack of substantive legislative achievements has revealed the talk-radio politics of the far right are incapable of forming a coherent governing agenda.

I keep thinking of how Obama kept predicting during his eight years of frustration that at some point the “fever would break” on the right. It never did. But history is an ironist. It turns out that the only way the fever could ever have broken is if the GOP actually got complete control of the government and … couldn’t do much of anything. The bluff has been extravagantly called. It’s one thing to rail against the “disaster” of Obamacare; it’s quite another, it turns out, to replace it.

All the right’s political power, we can now see, depended on being in permanent opposition, and never having to actually implement something. Their tax cuts for the very wealthy are tone-deaf; their resuscitation of the Laffer curve surreal. They’ve got nothing on health care but a return to the highly unpopular status quo ante. And they are caught between Trump’s desire to borrow even more to finance his tax cuts and the GOP’s resolute insistence throughout the Obama years that the debt was an existential threat. It’s quite amazing to watch this unfold and unravel in real time.

And here’s the thing: My suspicion is that if Clinton had become president, the fever would not have broken at all; it would have intensified. Her incompetence and indecision would have given the GOP even more political oxygen; a Republican House would have stymied her even more effectively than it did Obama; her unfavorables would have gone through the roof; and it could have been an ugly death spiral for the Democrats. (The latest polls showing considerable dissatisfaction with Trump nonetheless show that in a rematch, he would actually do better today against Clinton than he did last November.)

Instead, we have a manifest and brutal exposure of the stark promises Trump made, and of the incoherence and shallowness of so much of the Republican agenda. I still would never have risked putting this menacing clown into the Oval Office. But in the long run, if catastrophe doesn’t strike, it might even be better for the future health of our politics that Clinton is not president. Maybe the American people are not so crazy after all.

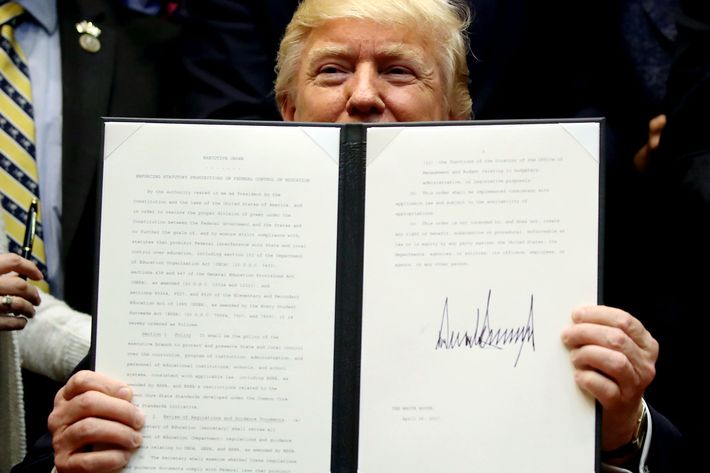

Here’s the scorecard of Trump’s first 100 days.

The Clinton counterfactual also makes me worry about Emmanuel Macron and France. He’ll almost certainly win — but his victory could well be pyrrhic. Why? Because his persona, background, and agenda are almost designed to polarize France still further, and thereby empower the reactionary right still further. He is not a centrist candidate on the core issues — the EU, immigration, Islamist terror, and national identity. He actually wants to accelerate European integration, he has attacked the notion that mass Muslim immigration is a problem for France, he embraces Angela Merkel’s impulsive invitation to more than a million Syrian refugees to come and live in the EU, he has called Islamist terrorism something to be lived with (even as France remains in a state of emergency), and he favors more Western involvement in tackling the chaos in the Middle East.

He is also a walking stereotype of the very globalist elites that many French have come to see as the enemy. A cute, cosmopolitan former banker who favors continuing many of President Hollande’s policies (but with more emphasis on the free market), he cannot help but be seen as the globalist candidate par excellence in a France increasingly drawn to nationalism. Forty-six percent of the vote in the first round went to candidates who were skeptical of free-market economics and the EU.

So we must fervently hope that Macron is able to have a successful presidency. Because if he fails — and he has no party in the assembly to lean on — Le Pen is waiting again in five years’ time. If the white regional working poor in France see no improvement in their lives, if the idea of traditional France continues to evaporate, and if the economic and social divide between the cognitive elite and the working poor deepens further, then what we are seeing now may be a pale version of the backlash ahead. Maybe I’ve read too much Michel Houellebecq, or maybe I’m too persuaded by the analysis of Christopher Caldwell, but I worry about the growing barometric political pressure in France. A Macron victory may not prevent, but merely postpone the deluge.

No, Andrew, whatever planet you are from. The Donald actually has a history of success. That would logically follow his taking control of the country. Unlike that down-low, crack smoking community activist that doubled our national debt. How do I get into community activist school? I also want to succeed with no credentials.

ReplyDeleteProbably overstating the obvious with this question but here goes anyway. If you decided to cross into Mexico illegally, would you be entitled to go to school, apply for any social entitlement programs, unemployment compensation, or own property, or get a driver's license? No? I didn't think so. So where are the protests about that?

ReplyDelete